The story of Samoan fire knife dancing begins long before anyone thought of wrapping a blade in fuel-soaked material and setting it alight. Its roots lie in ailao, an ancient exhibition where Samoan warriors demonstrated their skills with the nifo oti, a hooked war club or knife edged with sharpened teeth from sharks and other sea creatures. Between roughly 900 and 1200 AD, this weapon and the martial art around it rose to prominence, especially within the powerful Manuʻa and related Samoan polities.

Ailao as Warrior Exhibition

In ailao, the warrior did not simply stand and pose with the weapon. Instead, he moved dynamically, twirling, tossing, and catching the club in complex patterns that showcased dexterity and fearlessness. These displays could appear in processions, ceremonies, and other high-status occasions, and some accounts note that women—especially daughters of chiefs—also performed ailao at the head of ceremonial gatherings. What emerged was a fusion of combat readiness and performance, still anchored firmly in the warrior ethos.

Legend, Resistance, and Identity

Legend and history intertwine in this period. One famous narrative recounts how Samoan warriors used their weapons and clever tactics to drive out Tongan rulers who had established power in parts of Samoa. According to these accounts, warriors wrapped palm fibers around their nifo oti, lit them, and danced with them at night as part of a broader strategy to signal allies and coordinate a rebellion that ultimately pushed the Tongans back to sea. This story is tied to the origin of the chiefly title “Malietoa,” meaning “great warriors, well fought.”

Evolution of the Weapon

As centuries passed, the ailao tradition remained an important ceremonial and cultural element, even as the nature of warfare changed. In the modern era, contact with foreign tools and influences—such as long-handled knives used by whalers—shaped the physical design of the nifo oti and related implements. The hook and blade form became iconic, both as a weapon and later as a performance prop.

The Rise of Siva Afi

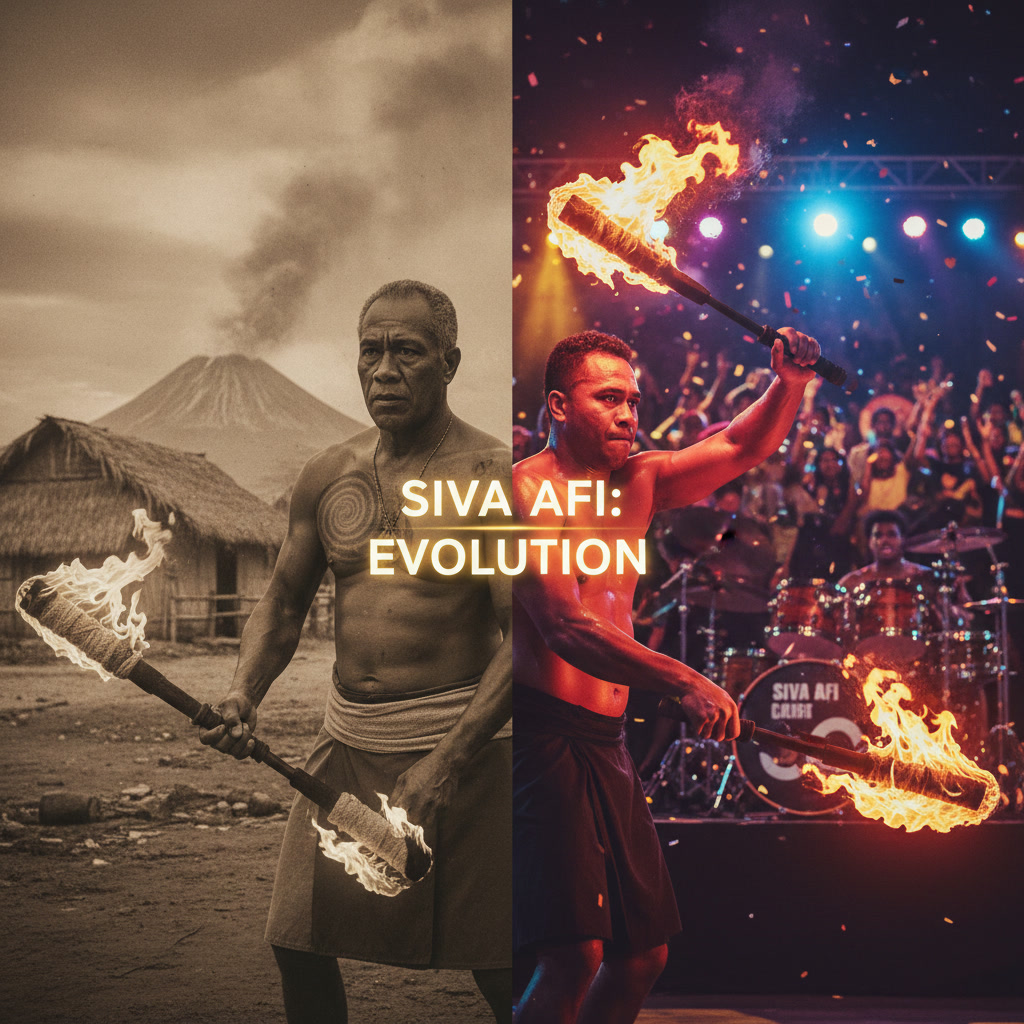

The shift from pure ailao to Siva Afi, the “fire dance,” intensified in the 20th century. Performers began adding flame to the exhibition, wrapping the ends of knives or clubs in flammable material and igniting them for night performances. Over time, especially in Hawaiʻi and other entertainment hubs, fire knife dancing evolved into a centerpiece act in Polynesian shows and luaus, with choreography, costuming, and music adapted for global audiences.

A Living Cultural Lineage

Yet beneath the spectacle, the cultural layers remain. The moves still echo that original warrior display, and the dance still carries stories of resistance, identity, and pride. This is the lineage that modern fire knife performers inherit—an unbroken thread from ancestral warriors to contemporary artists spinning fire before cheering crowds.

Mana Fire Knives and the Ongoing Story

Mana Fire Knives stands inside that history, not outside it. The team’s commitment to honoring ailao and Siva Afi as living cultural practices, rather than just stage tricks, is part of what defines their work. When audiences watch a Mana Fire Knives performance, they are seeing an art that has traveled from battlefield training grounds to ceremonial spaces to today’s stages without losing its heart. Readers who want to understand how each performer connects personally to that history can be encouraged to visit the Mana Fire Knives About page, where the group’s origins, values, and cultural ties are shared in detail.